The Universal Commerce Protocol: When Structured Data Gets a Rebrand

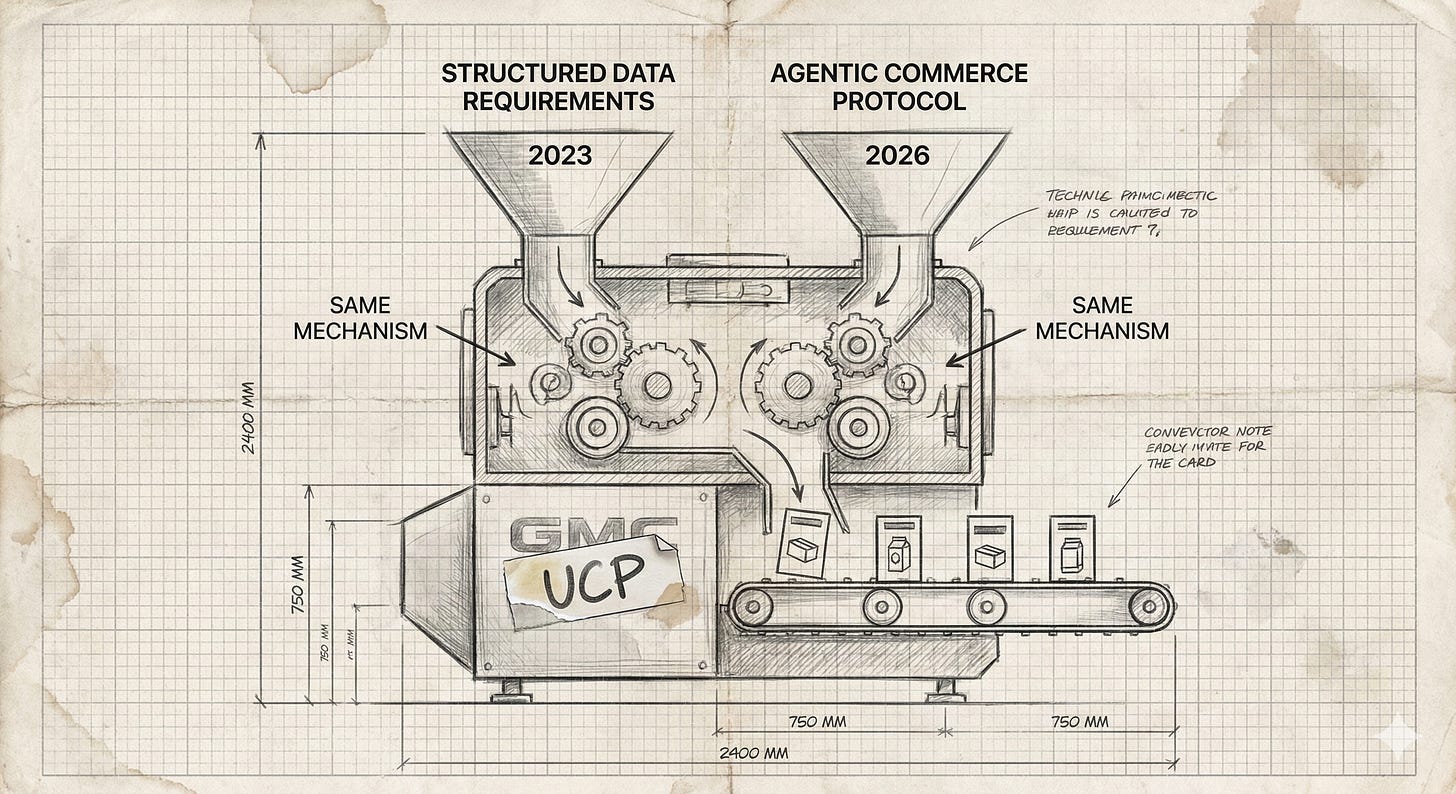

Structured data requirements haven't changed. The framing that makes retailers care about them has.

I’ve spent the past week watching reactions to Google’s Universal Commerce Protocol announcement at NRF. The responses ranged from breathless excitement about the agentic commerce future to detailed technical breakdowns of what UCP enables. What struck me most wasn’t what people were saying; it was what they weren’t questioning.

Strip away the agentic framing, and UCP is fundamentally about structured data. Again.

It’s not that UCP doesn’t solve real technical challenges—it does. It establishes a standardised way for AI systems to interact with product catalogues, inventory, and checkout flows without scraping HTML or guessing which <div> contains the price. For retailers who’ve actually maintained quality product feeds, UCP extends capabilities they’ve already been building toward.

But the more interesting story isn’t what UCP enables technically. It’s what Google’s learned about motivating compliance with requirements that have existed for years.

The Technical Reality: This Isn’t New (-sflash!)

UCP might be new as a formal protocol, but the concept isn’t. Google’s allowed brands to use the checkout_link_template field in Merchant Center to send users directly to checkout from search results since April 2025, with Shopify testing beginning in 2023. If you’ve already implemented this, UCP is the formalised wrapper around something you’ve been incrementally building toward.

The requirements underlying UCP—clean product data, accurate inventory, proper image specifications, operational details about shipping and returns—are identical to what’s been necessary for Merchant Center compliance all along. The fields merchants need to populate aren’t new. The organisational capability required to maintain that data hasn’t changed. The cross-departmental coordination between inventory management, marketing, and operations remains exactly as complex as it was before “agentic commerce” became the framing.

What has changed is how seriously retailers are taking these requirements.

The Motivation Problem Google Solved

Turns out the secret to getting retailers to care about structured data wasn’t better documentation; it was calling it “agentic commerce” and letting FOMO do the rest.

Google’s spent years publishing guidelines on feed quality, offering Top Quality Store programmes, and providing dashboards showing exactly where merchant data falls short. Adoption remained patchy. Feed quality issues that directly impacted visibility in Shopping results were treated as “nice to have” optimisation work rather than foundational business requirements.

Rebrand the same compliance requirements as “preparation for AI-driven commerce,” and suddenly data governance becomes a board-level priority. The underlying ask hasn’t changed—populate your product catalogue with accurate, comprehensive, structured information. But frame it as “you’ll be invisible to AI agents” rather than “you’ll rank poorly in Shopping,” and the urgency shifts entirely.

It’s brilliant positioning, honestly. The AI hype cycle is doing the motivational work that years of documentation couldn’t achieve.

Which would be fine—genuinely useful, even—if the shopping behaviour UCP enables actually existed at meaningful scale.

The Behaviour That Isn’t There

Google’s announcement assumes a world where consumers routinely delegate purchase decisions to AI agents. The technical infrastructure supports it. The structured data makes it possible. The protocol standardises it.

But do people actually want agents making these decisions on their behalf?

Amazon’s Alexa has been sitting in homes for years, periodically nagging about “items in your cart.” It’s used primarily for reordering things you already know you want—the same laundry detergent, the same coffee pods, the same predictable replenishment purchases. For anything requiring evaluation, visual assessment, or comparison, the voice interface fails not because of technical limitations but because humans prefer to look at things before buying them.

This isn’t speculation. Academic research on voice commerce adoption consistently shows that consumers exhibit what researchers call “algorithm aversion“ for subjective purchase decisions. They’ll trust an AI to calculate the fastest route or find the cheapest flight—tasks involving quantifiable optimisation—but actively resist algorithmic recommendations for anything involving taste, aesthetics, or personal preference. The reasoning is intuitive: consumers believe an entity that cannot experience a product cannot adequately recommend it.

There’s a reason Amazon’s product pages are dominated by user-generated photos rather than just manufacturer specifications. Structured data can tell you a camping chair supports 300 pounds and uses recycled materials. But consumers don’t trust structured data alone; they want visual verification from other humans who’ve actually used the product. They want to see how it looks in someone’s garden, how it folds, whether the fabric looks cheap or substantial.

This preference for visual validation isn’t a quirk—it’s a fundamental cognitive pattern. Research on screenless interfaces shows that consumers use voice to add items to a cart but wait to checkout until they can verify the item on a screen. The voice interface captures intent; the visual interface closes the transaction. Users aren’t abandoning voice because the technology fails—they’re abandoning it because seeing the product before committing feels non-negotiable.

Retailers are being asked to provide extensive structured data so AI agents can confidently recommend products that humans will still want to see pictures of before buying.

The confidence gap isn’t technical. No amount of protocol standardisation solves “I don’t trust an agent to pick the right camping chair for me without seeing it first.” That’s a human decision-making preference, not a data availability problem. UCP solves the technical challenge of agent-driven commerce whilst assuming away the behavioural challenge of whether anyone wants it for purchases beyond routine replenishment.

The Delegation Hierarchy Problem

Even if you accept that some purchases will happen through agents, the research suggests a clear hierarchy of what consumers will actually delegate.

Studies on AI-assisted purchase decisions consistently find the same pattern: consumers are comfortable delegating information retrieval (”What’s the price of X?”) and commodity reordering (”Reorder toothpaste”). They’re moderately willing to accept curation for low-stakes discoveries (”Find me a mystery novel”). They actively resist delegating decisions involving personal taste, social signalling, or emotional significance (”Buy a birthday gift for Mum”).

The higher the personal stakes, the stronger the resistance. Research on financial delegation to algorithms shows that consumers hold AI to a perfection standard they don’t apply to humans. If a friend recommends a terrible book, you forgive them. If an algorithm does it, you question the entire system’s competence. This asymmetric tolerance for error makes consumers reluctant to hand over decisions where getting it wrong carries consequences.

Google’s UCP infrastructure is built for comprehensive agent commerce. The actual consumer appetite is for agent-assisted commodity replenishment. That’s a meaningful gap between the protocol’s ambition and the behaviour it assumes.

The Measurement Problem You’re Not Being Told About

Even if agent-driven discovery does happen at scale, you’ll struggle to measure it properly.

If checkout happens within Google’s surfaces rather than on your site, your attribution breaks in new ways. The same transaction reports differently in GA4. Traffic that previously showed as organic search landing on product pages now shows as... what, exactly? Direct checkout completions with minimal session data? The “open protocol” language obscures a practical reality: the customer journey becomes less visible to you whilst remaining entirely visible to Google.

One merchant noted that traffic using checkout_link_template already bypasses traditional product page analytics. You can filter GA4 by checkout URL to see this traffic, but it’s a workaround, not a solution. With UCP, expect this measurement gap to widen. Google’s documentation doesn’t clarify how UCP transactions will appear in your analytics, which suggests you’ll be optimising for a channel with limited visibility into performance.

This is “AI optimisation is repackaged SEO with worse measurement“ made concrete. You’re being asked to invest in structured data compliance for a shopping paradigm that may not materialise at scale, and if it does, you’ll have reduced visibility into how it’s performing.

What Actually Matters Here

If you’re going to invest in UCP compliance—and if you want to maintain visibility in Google’s shopping surfaces, you probably should—do it because structured data quality was already table stakes for discovery, not because you believe agents will drive significant purchase volume.

The fundamentals haven’t changed:

Feed quality still determines visibility. Whether it’s called “optimising for Google Shopping” or “preparing for agentic commerce,” the requirement is identical: accurate, comprehensive product data maintained consistently across your catalogue.

Organisational capability remains the bottleneck. If your team couldn’t maintain clean Merchant Center feeds before UCP, the new protocol won’t suddenly make cross-departmental data governance easier. This requires coordination between inventory management, marketing, operations, and customer service, not just technical implementation.

Visual evaluation still drives purchase confidence. For anything beyond replenishment, consumers want to see products, compare options, and verify claims through user-generated content. Agent recommendations might narrow the consideration set, but purchase decisions still require human assessment. The research is consistent on this: consumers use voice and agents for the search phase of the funnel but require visual interfaces for the buy phase.

Measurement will get messier, not cleaner. Plan for reduced visibility into how transactions happen, even as you’re expected to optimise for the channel. The protocol being “open” doesn’t mean the customer journey data is accessible to you.

The one genuinely useful outcome of Google’s UCP announcement: if the AI hype finally motivates your organisation to treat structured data as a foundational capability rather than a tactical afterthought, that’s valuable regardless of whether agentic commerce happens at scale. Clean product data improves discovery across every channel, not just hypothetical AI agents.

Just don’t mistake protocol infrastructure for evidence of consumer demand. Google’s built the technical foundation for agent-driven commerce. Whether anyone actually wants to shop that way remains an open question—one that won’t be answered by how many retailers implement the protocol, but by whether consumers ever trust agents to make purchase decisions beyond reordering the same laundry detergent.

The vocabulary has changed. The fundamental challenge (getting retailers to maintain quality structured data) remains exactly what it’s always been. If calling it “agentic commerce” finally gets organisations to prioritise it, perhaps the rebrand was worth it after all.