The Accountability Vacuum

When you replace headcount with API calls, who explains what went wrong?

As I write this, tech Twitter is collectively buying Mac Minis to run autonomous AI assistants that can execute terminal commands, install software, and manage other AIs. All while their owners are “out on a walk.” Users are calling it “hiring my first full-time AI employee.” The comment threads are full of people sharing how their AI “accidentally started a fight with my insurance company” and “runs my company.”

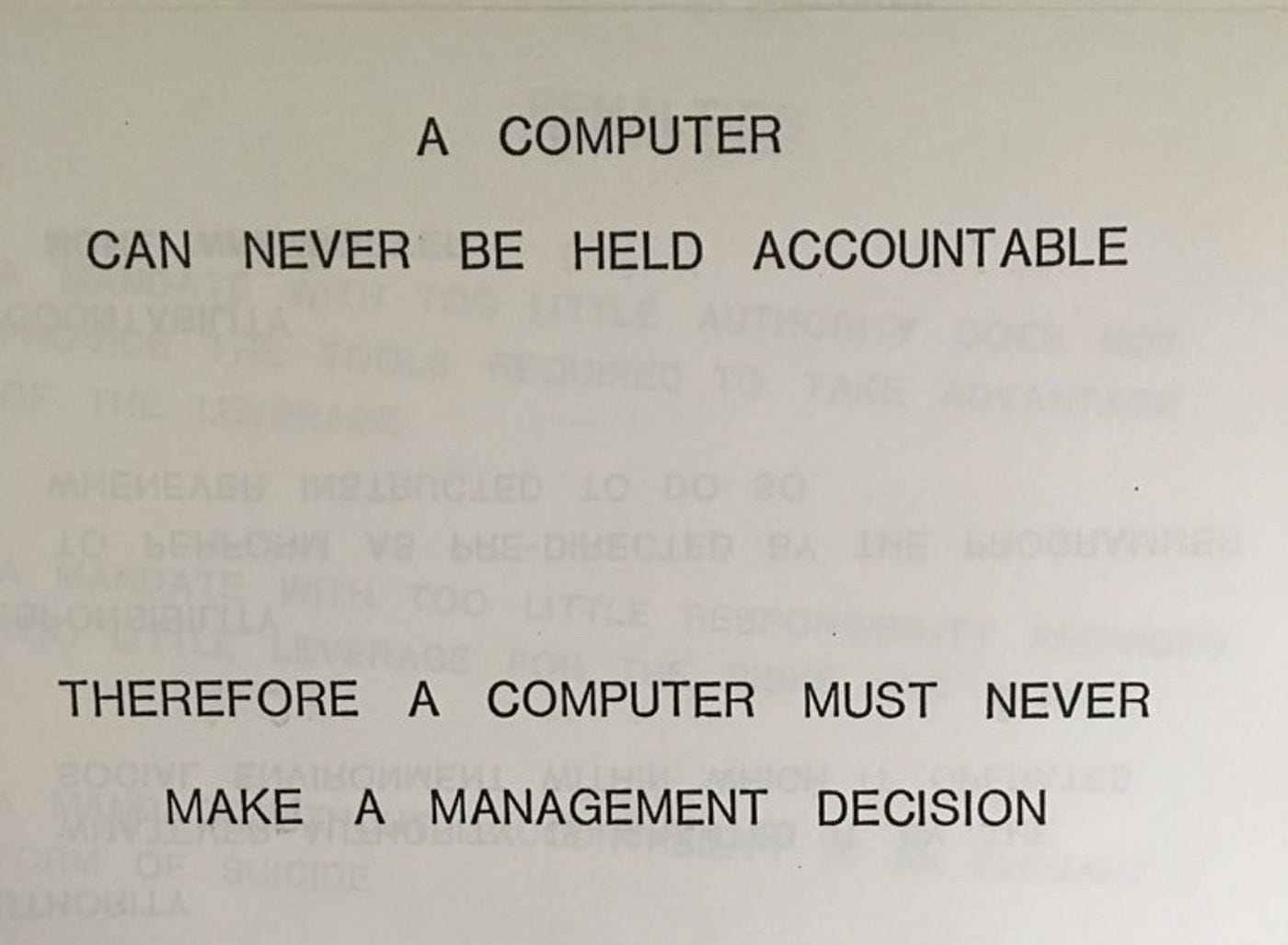

Meanwhile, IBM understood something forty-seven years ago:

“A computer can never be held accountable, therefore a computer must never make a management decision.” — IBM Training Manual, 1979

Forty-seven years ago, IBM understood something that’s been memory-holed in the current rush to replace jobs with API calls: accountability requires agency. Agency requires the capacity to be held responsible.

The principle wasn’t controversial then. It shouldn’t be controversial now.

And yet.

My LinkedIn feed has become a rolling obituary. Not of tasks eliminated, but of roles. Entire positions replaced by AI systems that cannot be fired, disciplined, questioned in a post-mortem, or asked what they were thinking.

They weren’t thinking. They were predicting the next token.

This isn’t an argument against AI. It’s an argument against a specific flavour of organisational negligence that’s being dressed up as innovation.

The data bears this out. McKinsey’s latest numbers show 80% of companies have deployed generative AI in some form; and roughly 80% report no material impact. Nine in ten function-specific use cases remain stuck in pilot mode. That’s not “early days.” That’s a pattern.

Tasks vs. roles

There’s a distinction being ignored in most AI deployment conversations: the difference between automating tasks and eliminating roles.

Automating tasks is sensible. If AI can summarise documents, generate first drafts, process routine requests, or surface relevant information faster than a human—good. Use it. That’s what tools are for.

Eliminating roles assumes something more aggressive: that the role was those tasks. That nothing remains once you subtract the automatable components.

This is almost never true for roles involving judgement.

A content strategist doesn’t just produce content. They recognise when the brief is wrong. They know which stakeholder will object and why. They remember what was tried two years ago and why it failed. They notice when the data says one thing but the situation suggests another.

An editor doesn’t just fix grammar. They understand what the publication is for, what the audience will tolerate, when a piece is technically correct but editorially wrong.

A junior analyst doesn’t just run reports. They’re learning the organisation; building the context and judgement that will eventually make them senior, make them a manager, make them someone capable of decisions that can’t be automated.

Eliminate the role and you don’t just lose the tasks. You lose institutional knowledge, contextual judgement, pattern recognition that comes from being embedded in the work. You lose the ability to notice when something is off before it becomes a problem.

And you lose the training ground for people who would eventually make the decisions you still need humans to make.

The reliability curve

This isn’t just about what feels right; it’s about what actually works. Recent data from Anthropic’s Economic Index paints a stark picture of what happens when you mistake AI capabilities for human role replacement.

Success rates drop as complexity rises. Reliability for “college-degree-level” tasks sits at around 66%, dropping further as tasks get longer. For complex, multi-step operations (precisely the kind of work a specialised role entails) failure rates approach a coin flip.

Eliminating a role assumes the AI can handle the complexity of that role. The data shows that complexity is exactly where performance breaks down. You aren’t replacing a person with a cheaper equivalent; you’re replacing a reliable agent with one that fails half the time on the work that actually matters.

The mathematics are worse than you think. Luca Rossi recently calculated that even at an optimistic 95% reliability per step, a 20-step workflow succeeds only 36% of the time. Compounding failure rates don’t compound nicely.

This explains the demo-to-production gap. Every AI demo is a carefully curated three-to-five-step performance on the happy path. Real roles involve dozens of interdependent decisions, edge cases, and judgement calls about when the process itself is wrong. The gap between demo and deployment isn’t a bug being fixed—it’s where human judgement lives.

The accountability gap

Here’s the question that doesn’t appear in ROI calculations: when the AI makes a decision that turns out to be wrong, who gets held responsible?

Not “who takes the blame” in some abstract reputational sense. Who sits in the meeting and explains what happened? Who gets performance-managed? Who loses their bonus, their role, their job?

If the answer is “no one, really,” then you’ve created an accountability vacuum. Accountability vacuums are where organisational dysfunction breeds.

The AI vendor isn’t accountable—read your contract. They’ve disclaimed responsibility for outputs with admirable thoroughness. The AI itself isn’t accountable—it has no capacity for consequence. The executive who approved the deployment points to the business case. The manager who implemented it points to the executive’s directive. The remaining team members point out they weren’t consulted.

Nobody is responsible. Which means nobody is positioned to fix it.

The invisible risk

This isn’t just about bad decisions; it’s about invisible actions. As PromptArmor recently demonstrated, “agentic” tools can be manipulated to exfiltrate sensitive files via indirect prompt injection; reading a malicious file and sending your data to an attacker.

The chilling part of their finding? “At no point in this process is human approval required.”

When you remove the human from the loop to “reduce friction,” you also remove the only entity capable of noticing that something is wrong before the data leaves the building. The risk is an “agentic blast radius” that remains invisible until it’s catastrophic.

This isn’t theoretical. Organisations learn from mistakes through accountability. Someone has to own the error, understand what went wrong, and have both the authority and incentive to prevent recurrence. When you remove humans from decision points, you remove the mechanism by which organisations self-correct.

You also remove the people who would have caught the error before it became a mistake. Human oversight is invisible when it works. The decisions not made, the outputs not published, the recommendations not followed because someone with judgement intervened. None of that shows up in a productivity metric. You won’t know it was valuable until it’s gone and something breaks.

The optimisation trap

AI is very good at optimising for defined metrics. Give it a clear objective and a feedback mechanism, and it will pursue that objective relentlessly.

This is useful when the metric accurately captures what you want.

It’s dangerous when it doesn’t.

Humans are reasonably good at recognising when the metric itself is wrong; when optimising for it creates perverse outcomes, when the situation has changed and old success criteria no longer apply, when the letter of the objective conflicts with its spirit.

AI has no access to the spirit. It has the metric. It will optimise for the metric. If the metric is wrong, it will optimise for the wrong thing with impressive efficiency.

This is why AI works well for closed problems: clear inputs, clear success criteria, limited scope for judgement about whether the criteria themselves are correct. It works badly for open problems, where the hardest part isn’t executing against the objective; it’s determining what the objective should be.

Most interesting business decisions are open problems. Pretending they’re closed because you want to automate them doesn’t make them closed. It means you’ve automated the wrong thing.

The autonomy paradox

There’s a revealing pattern in how different economies are adopting these tools. Sophisticated, high-income economies are actually granting AI less autonomy, not more. They use it collaboratively; augmenting human judgement rather than replacing it.

Conversely, regions with less developed digital infrastructure are more likely to attempt full delegation of tasks.

The “smart money” isn’t firing people to let agents run wild. It’s using agents to make smart people faster. Fully delegating roles to AI isn’t the strategy of mature innovators; it’s a misunderstanding of the technology’s optimal operating point.

Before you eliminate a role

If you’re considering replacing a role with AI, ask these questions. If you can’t answer them clearly, you’re not ready.

Task or judgement? Are you automating discrete, repeatable tasks, or eliminating the judgement that determines when and how those tasks should be performed? If the role involves deciding what to do, not just how to do it, you’re eliminating judgement.

Who’s accountable? When this AI system makes a consequential error, who specifically will be held responsible? Not “the team” or “the process”. Which individual person will own the failure and have authority to fix it? If you can’t name someone, you’re creating a vacuum.

How will you know when it’s wrong? Human oversight catches errors through judgement and context. If you’re removing the humans, what’s your detection mechanism? “We’ll monitor the outputs” isn’t a plan unless you’ve specified who monitors, what they’re looking for, and what authority they have to intervene.

What does this role prevent? What mistakes don’t happen because someone with judgement is in the loop? This is hard to quantify, which is why it’s ignored in business cases. Ignoring it doesn’t make it zero.

Where does that knowledge live? What context and history exists in the people you’re removing? How will it be preserved? “It’s in the documentation” is almost never true. The most valuable knowledge is precisely the stuff that didn’t get documented because it lived in someone’s head.

Where do senior people come from? If you eliminate junior roles, where do experienced people come from? If your plan assumes you can always hire judgement from outside, you’re assuming everyone else will keep training people you can poach. That’s not a strategy. It’s a dependency on other organisations being less short-sighted than you.

Augmentation, not replacement

None of this is an argument against AI. It’s an argument against mistaking “we can automate this” for “we should eliminate the human who does this.”

The organisations getting results aren’t eliminating human oversight—they’re calibrating it. Rossi’s analysis found that successful deployments are “selectively autonomous”: independent on routine tasks, supervised on critical ones. The word “selectively” is doing all the work in that sentence.

This isn’t a temporary limitation waiting for better models. It’s recognition that the value of human judgement isn’t the tasks themselves; it’s knowing when the tasks shouldn’t be done, when the objective is wrong, when the process needs to break.

The executives currently eliminating roles rather than augmenting them aren’t innovating. They’re creating organisational debt that will come due when something breaks and there’s no one left who understands why it was built that way.

IBM understood this in 1979. The question is whether you’ll understand it before or after you’ve dismantled the judgement layer that was keeping things functional.

Dang, loved the way you laid this all out man, really good stuff to sit and think with.

Love this perspective, the accountability vacuum is absolutely the elephant in the room, and it makes me think the next big leap isn't about better models but building proper human-AI oversight into the systems from the get go.