Stop Learning SEO. Start Learning SEO

The best SEO education doesn't mention SEO once.

People ask me where they should go to learn SEO. My answer disappoints them.

“Forget about SEO blogs and resources.”

They expect a reading list. A curated collection of industry newsletters, maybe a podcast recommendation, possibly a course with a certificate they can add to LinkedIn. Instead I tell them to read a book about usability from 2000 and study accessibility guidelines that predate Google’s IPO.

This isn’t gatekeeping. It’s directions to the actual gate.

The SEO content problem

The SEO industry has a content problem, which is ironic given that content is supposedly what we’re experts at optimising.

Most SEO resources exist to generate traffic for SEO agencies. They’re written to rank, not to teach. The incentive structure guarantees that what you’re reading is optimised for impressions, not for making you competent. Every “complete guide to SEO in 2026” is really a “complete guide to what we think will get us leads in 2026.”

This creates a bizarre feedback loop. People learn SEO from content designed to demonstrate SEO, which teaches them that SEO is about creating content designed to demonstrate SEO. Somewhere along the way, the actual discipline—making websites work well for humans and machines—gets lost in the recursion.

And then there’s the freshness treadmill. SEO blogs have to keep publishing. Google makes an announcement, and suddenly everyone needs a hot take. Half of what gets written is speculation dressed as analysis, repackaged within 48 hours as “what we know so far” and within a week as “the definitive guide.” By the time something is definitive, Google has moved on and we’re speculating about the next thing.

You can spend years reading SEO content and come away knowing a lot about what Google said in various blog posts but very little about why websites work or don’t work.

What to learn instead

The disciplines that actually matter predate SEO and will outlive whatever Google does next. They fall into three categories:

how the web works

how humans work

how to think about problems

SEO is supposed to be the intersection of all three, but the industry spends most of its time ignoring the foundations.

How the web works

Web development best practices. Not “technical SEO”—actual web development. How browsers render pages. How servers respond to requests. What happens between a click and a painted screen. The performance work Google’s been pushing for years (Core Web Vitals, mobile-first indexing, page experience signals) is just web development best practices rebranded with a ranking incentive attached. If you understand how the web works, you understand what Google is measuring without needing someone to tell you.

Web Accessibility. The Web Content Accessibility Guidelines exist because the web should work for everyone. Following them makes your site work better for screen readers, keyboard navigation, and—surprise—search engine crawlers. The overlap isn’t coincidental. Crawlers are, functionally, blind users who can’t execute JavaScript reliably. When accessibility advocates spent decades fighting for semantic HTML, they were also accidentally building the foundation for technical SEO. You’re welcome.

Information retrieval. This is the academic discipline search engines are built on. Precision versus recall. Relevance ranking. Query understanding. The trade-offs between returning exactly what someone asked for and returning what they probably meant. You don’t need a computer science degree, but understanding these concepts at a basic level explains why Google makes certain decisions that otherwise seem arbitrary. When Google “fails” to rank your page, they’re usually making a retrieval trade-off you haven’t considered.

How humans work

Usability. Steve Krug’s Don’t Make Me Think was published in 2000. It’s still the best introduction to how people actually use websites, as opposed to how we imagine they use them. The core insight—that users don’t read, they scan; they don’t make optimal choices, they satisfice; they don’t figure out how things work, they muddle through—explains more about bounce rates and engagement signals than any heatmap tool.

Jakob Nielsen’s heuristics. Ten principles from 1994 that explain why most websites fail. Visibility of system status. Match between system and real world. User control and freedom. These aren’t SEO concepts, but they explain why some sites convert and others don’t. And since Google has spent twenty years trying to measure whether sites are actually good, understanding what “good” means tends to help.

Information Architecture. How content should be organised so humans can find what they need. This isn’t about siloing keywords or building topical authority—it’s about understanding how people categorise information and navigate structures. The card sorting studies from the 1990s are more useful for site structure decisions than any “internal linking strategy” post written last month.

Content design. Sarah Winters built the content discipline at GOV.UK and wrote the book on it—literally. Content design asks “what does the user need to do?” before “what should we write?” It treats content as problem-solving, not publishing. This is the opposite of how most SEO content gets produced, where the question is “what keywords should we target?” and the user’s actual needs are reverse-engineered from search volume.

How think about problems

Findability. Here’s the irony: there’s already a discipline that describes what SEO is supposed to do, and it’s not called SEO. Peter Morville’s Ambient Findability (2005) frames the problem of “how do people find things?” as a design challenge spanning search, navigation, wayfinding, and information architecture. Findability is SEO with the Google-specific tactics stripped out—the actual problem, not one platform’s implementation of it. When you understand findability as a discipline, you stop treating search engines as the centre of the universe and start treating them as one channel among many.

Strategic thinking. Most SEO “strategies” aren’t strategies at all. Richard Rumelt’s Good Strategy/Bad Strategy provides the clearest framework for understanding the difference. A strategy has a diagnosis (what’s actually going on), a guiding policy (the approach you’ll take), and coherent actions (specific steps that reinforce each other). “Rank higher for commercial keywords” is a goal. “Build more backlinks” is a tactic. Neither is a strategy, and confusing them is why so much SEO work feels like activity without progress.

This matters because SEO decisions don’t happen in isolation. They compete for resources with other priorities. If you can’t articulate why a technical fix matters more than a new feature, or why content investment should come before link building, you’re not doing strategy—you’re doing advocacy for your department. Rumelt teaches you to diagnose the actual situation, not the situation you wish you had.

Why this works

Google’s stated goal is to surface the best results for users. You can argue about how well they achieve it, but the goal itself points in a direction: make good websites.

The problem with learning SEO from SEO resources is that you learn to optimise for the measurement instead of the thing being measured. You learn to game signals rather than create the quality the signals are trying to detect. This works until it doesn’t, and then you need a new tactic.

The foundational disciplines don’t have this problem. Usability principles don’t change when Google updates an algorithm. Accessibility requirements don’t pivot based on what’s ranking. Information architecture isn’t subject to speculation about what the September core update might have targeted.

When you understand why Google values something (because it indicates quality to users) you can reason from first principles about any change they make. When you only know that Google values something, you’re stuck waiting for someone to tell you what to do next.

This is why people who understood usability, accessibility, and content design never needed to be told about E-E-A-T. When Google published guidelines about demonstrating experience, expertise, authoritativeness, and trustworthiness, it wasn’t news—it was a description of what they’d been doing all along. The SEO industry treated it as a new ranking factor to optimise for. Everyone else recognised it as table stakes.

This is also what separates experienced SEOs from people who’ve simply done SEO for a long time. Seniority isn’t years served—it’s variants of the same problem solved across different contexts. A senior SEO has seen the same underlying issue manifest in enterprise e-commerce, in media publishing, in SaaS documentation, and recognises the mechanism even when the surface symptoms look nothing alike. That pattern recognition doesn’t come from checklists. It comes from understanding why things break.

Courses and certifications can teach you what to do. They can’t teach you what to do when the standard answer doesn’t apply—which is most of the time, if you’re working on anything interesting. You can memorise every best practice in the industry and still be useless the moment something breaks in a way the checklist didn’t anticipate. The people who get stuck are the ones who learned what to do without ever understanding why it works.

This has always been true. What’s changed is the cost of not understanding.

AI can execute checklists faster and more consistently than any human. If your value proposition is following documented procedures, running through audit templates, chasing ranking tricks; you’re competing with something that doesn’t sleep and doesn’t bill by the hour. The button-pushers and checklist-followers are already being replaced. Not by some future technology, but by tools that exist today.

What AI still struggles with is reasoning through novel problems. It can’t look at a site losing traffic and figure out which of twelve possible explanations actually applies to this specific situation, given this specific business context, with these specific constraints. That requires understanding mechanisms, not memorising outputs.

That’s the job. That’s always been the job. The difference is that now the alternative is obsolete, not just less effective.

The uncomfortable implication

If the best SEO education comes from UX, accessibility, and web development, what exactly is the SEO industry contributing?

Coordination, mostly. Someone needs to translate between disciplines, prioritise work based on impact, and make the business case for technical improvements that would otherwise languish in backlogs. There’s value in that.

But the knowledge itself? The foundational understanding of how to build good websites? That comes from people who weren’t trying to rank anything. They were trying to make the web work.

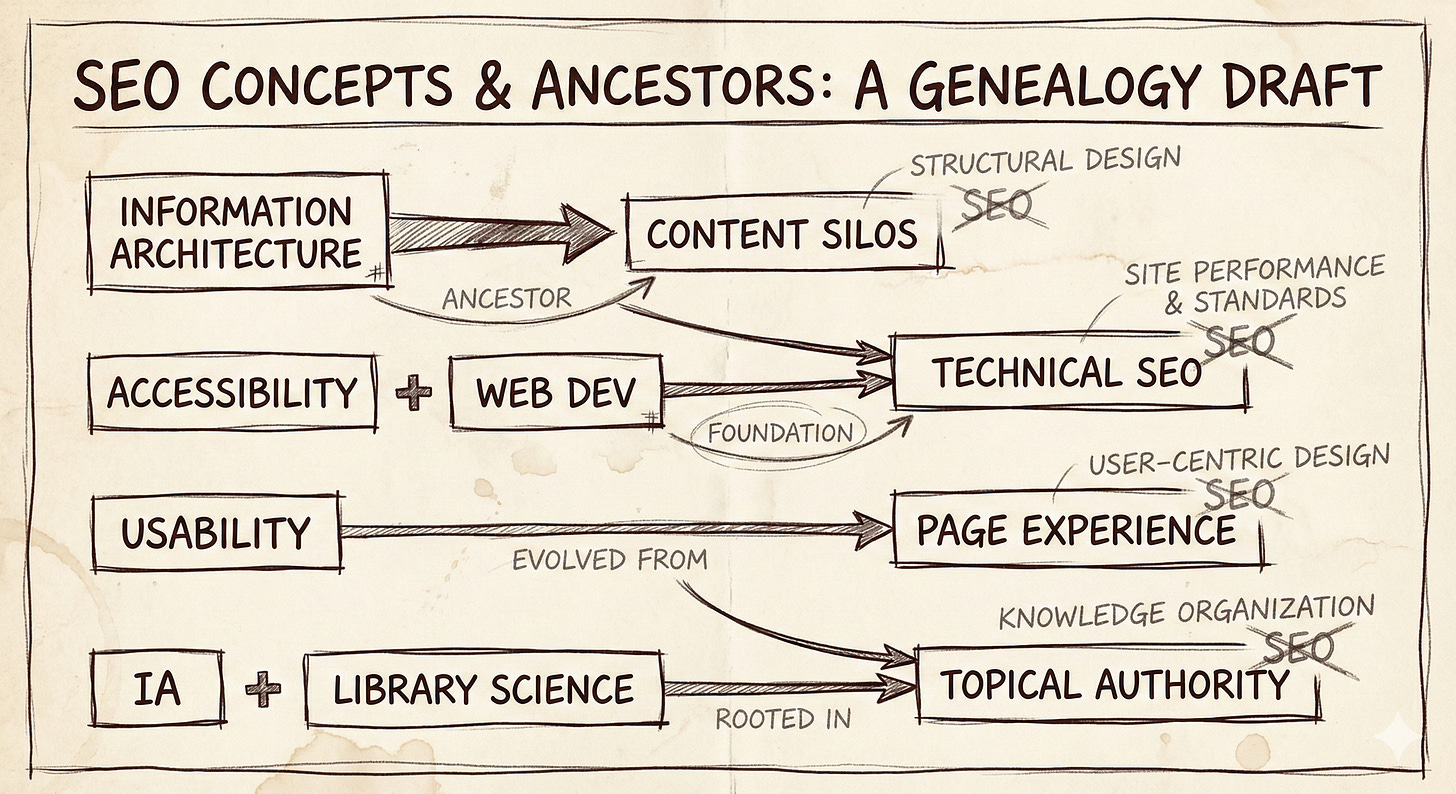

The SEO industry took those principles, repackaged them with keyword-focused framing, and sold them back at markup. Information Architecture became “content silos.” Web Development’s Graceful Degradation became “JavaScrip SEO.” Usability became “page experience optimisation.”

I’m not saying there’s no original thinking in SEO. There is. But the core competencies—the stuff that actually matters when the algorithms change and the tactics expire—came from somewhere else.

If you want to learn SEO, go learn that instead.

This is why my own website’s knowledge base lists foundational books—Krug, Rumelt, the IR textbook—before any “Learn SEO” resources. The order isn’t accidental.

Reading list (none of it about SEO):

Transparency Note: If you buy through the links below, I may earn a small commission at no extra cost to you. This helps support my work—thank you!

How the web works:

High Performance Web Sites — Steve Souders

Introduction to Information Retrieval — Manning, Raghavan, and Schütze (free online)

How humans work:

Don’t Make Me Think — Steve Krug

10 Usability Heuristics for User Interface Design — Jakob Nielsen

Information Architecture for the World Wide Web — Rosenfeld and Morville

Content Design — Sarah Winters

Designing with the Mind in Mind — Jeff Johnson

How to think about problems:

Ambient Findability — Peter Morville

Good Strategy/Bad Strategy — Richard Rumelt

When you’ve finished those, you’ll understand more about what makes websites rank than most people who’ve spent years reading SEO blogs.

That’s not an insult to SEO blogs. It’s a reflection of what they’re optimised for—and it isn’t teaching you.