Publishing Everything Is a Terrible Business Strategy

The traffic bargain was a lucky externality, not a contract. It's time to stop mourning it.

Many of the people I’ve been chatting with lately keep circling the same question: if AI systems consume your content without attribution, traffic, or backlinks, why would anyone keep producing?

It’s a fair question. It’s also the wrong framing.

The transaction was always asymmetric

The implicit bargain of web content—”I let you index my work, you send me traffic”—was never actually a contract. It was a side effect of how retrieval worked. Search engines needed to send users somewhere because they couldn’t answer questions directly. That barrier is getting demolished.

What we’re witnessing isn’t theft. It’s the end of a lucky externality that content producers mistook for a guaranteed exchange. Sorry, but nobody signed anything.

You can’t retrieve what’s been absorbed

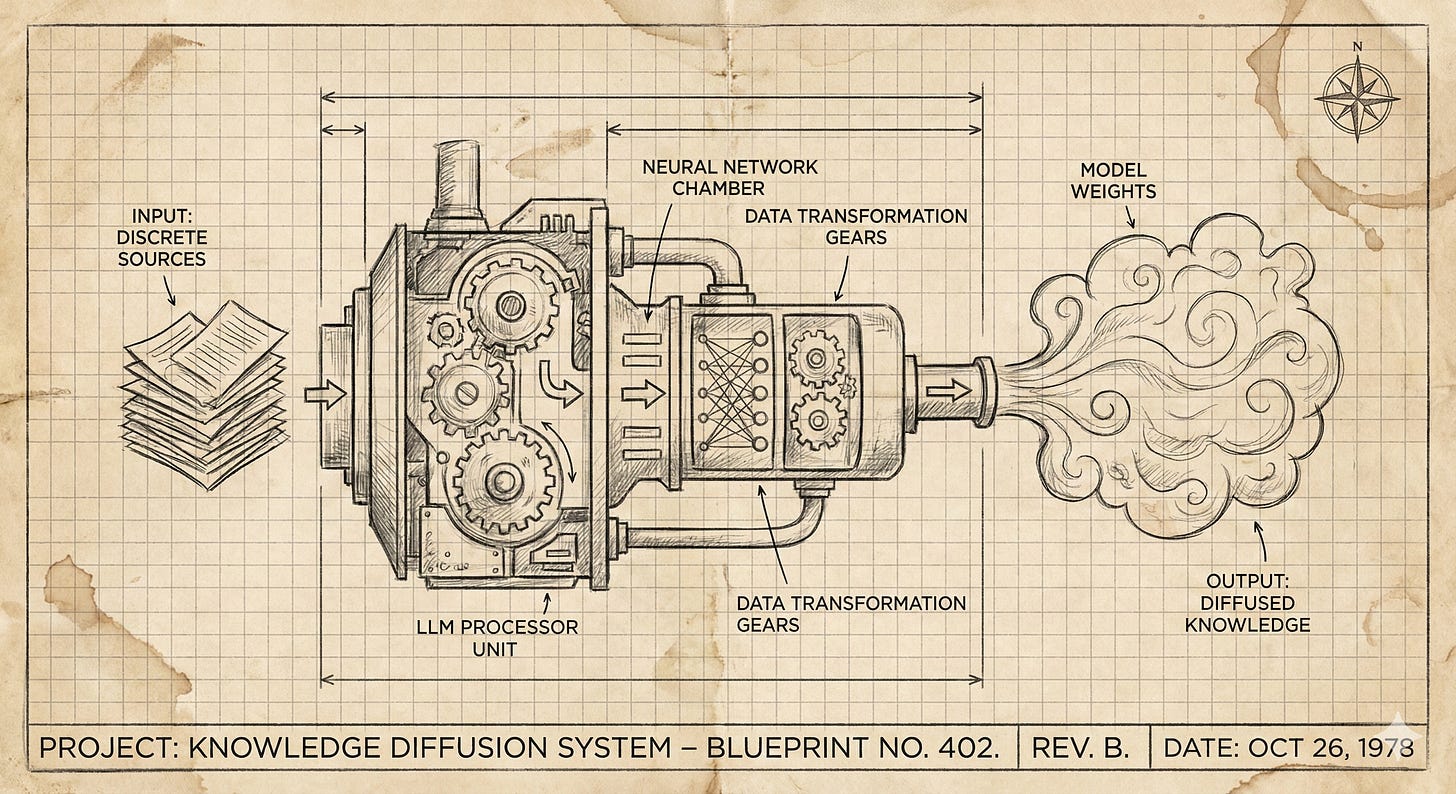

Once your content enters an AI system’s training data, it doesn’t exist there as a discrete, citable source. It becomes part of the model’s general capability—diffused, recombined, fundamentally transformed. This is mostly irreversible, and there’s no file to link back to. The original piece has been metabolised into something that no longer depends on its source.

This isn’t a bug that better citation systems will fix. It’s the architecture.

Current AI systems often can’t tell you where specific knowledge originated because that knowledge has been stripped of provenance during training. Asking for attribution from these systems is like asking someone to cite which conversations shaped their personality. Good luck with that invoice.

The degree to which retrieval-augmented generation (RAG) systems might address this in specific contexts remains unclear—they can cite retrieved documents, but that’s a fundamentally different mechanism from attributing absorbed training knowledge. Don’t hold your breath waiting for a technical fix that makes everyone whole.

The strategic question you should actually be asking

The conversations I keep having assume content production remains the core activity worth protecting. But I think the strategic lens needs adjusting: what content should you produce at all, and for whom?

If your content exists primarily to rank for keywords and capture traffic, you’re competing in a game whose rules have already shifted. AI systems can produce adequate keyword-targeted content faster and cheaper than you can. The transaction where you’d hire a writer for quick, serviceable content now routes to AI instead. The junior copywriter’s competition isn’t another junior copywriter anymore—it’s a subscription that costs less than their lunch.

The content worth producing is the work AI cannot do:

Research that requires synthesis across non-public sources — conversations, proprietary data, original investigation

Expertise that compounds — deep specialisation that builds on itself in ways generic models can’t replicate

Perspectives that carry risk — positions that require judgment, stake, and accountability

Everything else is increasingly commodity. Fighting for attribution on commodity content is fighting for table scraps. And the table scraps aren’t even that good.

Walled gardens aren’t the answer either

Some conclude that paywalls have already won. That’s one outcome. But it’s worth noting what you lose behind a wall: discoverability, influence, the ability to shape how your expertise is understood in the broader ecosystem. Congratulations, you’ve protected your content. Nobody’s reading it, but it’s safe.

I think the more useful framing is this: be thoughtful about what you give away for free. Not everything. Not nothing. Strategic disclosure that establishes authority without surrendering your full value proposition.

This means:

Publishing insights that demonstrate capability without revealing methodology

Creating content that generates demand for expertise rather than satisfying it completely

Treating public content as marketing for services, not as the product itself

If you’re putting out everything of value you have, eventually you run out. And then what? You can argue that you’ll keep doing research, keep generating new insights—and if you can sustain that, brilliant. But most businesses can’t maintain that pace indefinitely. Racing to publish every insight before competitors do starts looking like a race to the bottom. A race nobody asked you to enter, by the way.

The specialisation imperative

The consistent thread through this shift: generalists producing general content for general audiences face the biggest challenges. The path forward is specificity.

I’ve learned more from people who aren’t visible on social media than from most of the names that dominate the feeds. Deep expertise doesn’t require a platform. But increasingly, a platform without deep expertise is just noise. Loud, well-marketed noise—but noise.

Become the person who knows a domain so thoroughly that AI systems would need to train specifically on your work to replicate your capability—and even then would lack the ongoing judgment and contextual awareness you bring. Be the person others think of when they encounter a specific problem. Not “someone who writes about SEO,” but “the person you call when your indexing is inexplicably broken and you’ve tried everything.”

This isn’t comfortable advice for people who’ve built careers on volume and breadth. But the alternative—demanding that AI systems develop attribution mechanisms they’re not architected to provide—is hoping for a solution that may never arrive. You might be waiting a while.

What actually changes

Stop expecting reciprocity from systems that don’t operate on reciprocity. Start treating content strategy as a subset of business strategy rather than the other way around.

The question isn’t “how do we force AI to cite us?” It’s “what do we produce that remains valuable regardless of whether AI cites us?”

That’s a harder question. It’s also the only one worth spending time on.

Eh. I don't know. The solution is in the middle probably. Starve the beasts, give them some morsels. Keep the main course for the real human guests.

I run a personal website where I share my knowledge, perspectives, and creations not in search of revenue but as a form of self expression. I'd like to respond to your article point by point.

1. "The implicit bargain of web content—”I let you index my work, you send me traffic”—was never actually a contract." --- Full agree

2. "What we’re witnessing isn’t theft." ---Hard disagree there. Just because a contract wasn't signed. Copyright and authorship are codified by legal principle without the need of a contract. The act of a person producing something new (image, audio, text) implies authorship and copyright, and while I am no legal expert, authorship and copyright go a long way to establish ownership. And I don't know about you but it is natural to want to defend what you own.

3. "Current AI systems often can’t tell you where specific knowledge originated because that knowledge has been stripped of provenance during training." I wish I could respond with a GIF and that GIF would be Leonardo DiCaprio whistling, snapping, and pointing at the screen, you definitely know the one. "Knowledge stripped of provenance" is the original sin, if this wasn't a malicious choice, it reflects the unprepared nature of the LLM rollout. We live in the era of attribution automation, whether it's content ID, affiliate and tag managers...I could go on. If LLM training did not account for provenance then it points to two possibilities: 1. LLMs are trained with copyright and attribution circumvention by default (malicious) 2. LLM training was designed for research and testing purposes in a closed and controlled environment which was then coopted and exploited by malicious actors who extracted it from a research context without due dilligence and unleashed it publicly because of the sociopathic and myopic greed.

However, what is a red line for me, especially when it comes to knowledge systems and learning as a human being, is the lack of provenance by design (whether malicious or underbaked). My english, history, geography, and social sciences teachers in middle, high school and college would have crucified me (and rightfully so) for not citing the sources I used to develop research and arguments. Any information system that does not accurately cite, and more importantly, has been trained to circumvent attribution or provenance is fundamentally untrustworthy, vulnerable to manipulation, and profoundly harmful. This point says so much about LLMs, unreliable by design, and an abdication of responsibility (this last point applies to all the business leaders who have myopically foisted LLMs across society inspite of their colossal shortcomings and documented harms -- LLMs are the mechanism through which business leaders circumvent accountability).

4. The content worth producing is the work AI cannot do: ... ---agree with these points BUT you miss a crucial one: self-expression...sure not exactly a business or LinkedIn friendly term but this was the point of the web before it was ruined by big business. Before the rot economy growth cult siloes of social media, the web functioned as Gutenberg's second coming, anyone could publish. The cost and speed of expressing oneself and accessing information was drastically slashed. Sure, search engines came along and commodified the convenience of finding but at the end of the day, the purest expression of the internet is a series of interlinked files (who knew that "the series of tubes guy was onto something", if you know you know). More crucially, in the same way that Grok cannot respond to a request for comment as to why the xAI LLM produces CSAM in the same way that a dedicated human spox can, LLMs cannot express themselves because a language model does not have agency. Any crude attempts at anthropomorphizing a language model reveal more about the person doing the anthropomorphizing than about the LLM.

Aside from that, I agree with the rest of your article with the caveats expressed above (spelling mistakes, warts and all)